In the cards: Library partners work together to solve mysteries of rare tarot deck

Although in some circles tarot cards are divination tools for predicting the future, the tarot cards in the library’s collection are opening windows into the past.

For the past five years, and throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the library has collaborated internally and partnered internationally to study the world’s three earliest 15th-century Italian tarot (or tarocchi) decks. One of these decks is the Visconti di Modrone deck, held in the Cary Collection of Playing Cards at Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Dating from ca. 1440–45, it is one of the oldest of the three.

Yale’s project team—Marie-France Lemay, head of paper and photograph conservation at Yale Library; Timothy Young, former curator of Modern Books and Manuscripts and curator of the Cary Collection at Beinecke Rare Books and Manuscripts; and conservation scientists Richard Hark, Marcie Wiggins, and Anikó Bezur from Yale’s Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage (IPCH)—set out to discover what these ornate hand-painted cards reveal about their makers and materials. Each of them brought unique skills and expertise to the task.

“Working with cultural heritage objects has been compared to a three-legged stool,” said Hark. “You have art historians with a specific specialty, conservators of different stripes, and conservation scientists. It’s the synergistic combination of all three working together, bringing their different perspectives and expertise to bear on figuring things out, that allows us to achieve the most satisfying and complete results.”

The library team also collaborated with experts at various cultural institutions who were examining the other two known, partial decks held in New York and in several locations in Italy. Staff at the Morgan Library & Museum, the Network Initiative for Conservation Science (NICS) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York; the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC; the Art Institute of Chicago; and the Centro per la Conservazione ed il Restauro dei Beni Culturali “La Venaria Reale” in Turin are also members of the current team, contributing both expertise and access to analytical equipment to the collaborative effort. This 13-person, multidisciplinary partnership is working together to determine the cards’ history, material construction, and relationship to each other.

The partners have given themselves the name Team Tarocchi.

Although literature describing the historical and art historical research about illuminated tarocchi cards exists, there is little published technical and material research. “Answering technical questions about the decks’ composition would fill in their art historical record,” and “spark further exchanges among professionals in the cultural heritage field,” four of the team members wrote in a recent paper submitted for publication.

The ambitious work is ongoing—Team Tarocchi meets monthly via Zoom—but the collaboration of colleagues at these institutions has already resulted in a large amount of data to “record, interpret, and share.”

Tarocchi

Tarocchi was a popular trick-taking card game in Europe during the 15th century and is still played today. (The cards began to be used for fortune telling only in the 18th century.) A typical complete tarocchi deck contained 78 cards with trump (trionfi) cards, face (or court) cards and pip (or numeral) cards in four suits: batons, cups, swords, and coins.

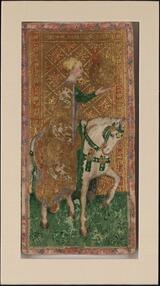

The library’s Visconti di Modrone deck, although having only 67 surviving cards, is unique in that it includes female Knight and female Page cards for each suit. “These additional female cards have suggested to some that this deck had perhaps been commissioned for a woman,” Lemay said. “The other two sets do not have those female court cards.” The library’s deck also contains cards representing the three theological virtues: Faith, Hope, and Charity. The original, full deck likely would have had a minimum of 89 cards.

The Morgan Library has 35 cards from the most complete partial deck, which is known as the Visconti-Sforza or Colleoni-Baglioni deck; 26 cards from that same deck are held by the Accademia Carrera in Bergamo, Italy, and 13 are in a private collection in Bergamo. Six of the cards in the Visconti-Sforza deck, clearly produced by a different hand, are dated ca. 1465–70. These six cards are usually referred to as “replacement cards” because they are thought to have been created to replace cards that were lost, damaged,or destroyed. The third deck, which has the fewest surviving cards, is the Brambilla deck at the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan, Italy.

These three early decks, created between ca. 1440 and ca. 1480, are together known as the Visconti-Sforza decks, named for the Italian aristocrats who commissioned and owned them: Filippo Maria Visconti, duke of Milan, and Francesco Sforza, Visconti’s son-in-law. Stamped gold coins (fiorini)—found on cards in two of the decks and similar to coins minted during Visconti’s reign—have led scholars to believe the cards were created before Filippo Maria’s death in 1447.

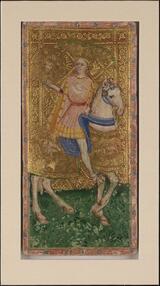

These ornate decks have generally been attributed to the Northern Italian artist Bonifacio Bembo and his workshop, but the most current art historical scholarship suggests that the Yale cards may be the work of Bonifacio’s older brother, Andrea. Bonifacio Bembo was known for his multimedia work in wall painting, panel painting, and manuscript illumination.

“It was not uncommon for artists at the time to be fluent in one than more technique,” Lemay said, “Our hypothesis is that these cards are a sort of hybrid between panel and manuscript painting because we can see techniques from both in use.”

The opening bid

Lemay first encountered the library’s Visconti di Modrone cards when the Metropolitan Museum of Art asked to borrow some of the cards in 2008. As she documented and prepared the cards before shipping them to the museum, she grew curious and began researching the published literature, noting then that there was little technical information about them.

In 2015, the Metropolitan again asked to borrow cards, this time for its exhibit “The World in Play: Luxury Cards 1430–1540,” which was opening at the Cloisters in January 2016. Lemay couriered the cards personally in order to supervise the unpacking and check their condition upon arrival at the museum. During the installation, Lemay met Francisco H. Trujillo, the Drue Heinz Book Conservator at the Morgan Library & Museum. Trujillo had couriered the Morgan’s cards for the same exhibit. The two began discussing the similarities between the Yale and Morgan decks. Later that year, they met again at a conference and started discussing the possibility of an in-depth comparative technical study of their institutions’ cards.

Team Tarocchi

Two years later, the work began. By this time, IPCH had been in existence for several years and had built its capacity for conservation science under the direction of Anikó Bezur. In 2018, IPCH, Yale Library, and the museums at Yale jointly purchased a Bruker M6 Jetstream scanning X-ray fluorescence (XRF) system.

Now that Yale had this increased technical capability, Lemay contacted Trujillo again. They decided to compare seven cards that both the Yale and Morgan sets had in common. Young was able to provide funds from the Cary Collection to pay for the shipping of the Morgan cards to Yale so that the same type of analysis could be conducted on both sets.

The Morgan also secured the assistance of NICS at the Metropolitan Museum to conduct the analysis of another portion of its deck. Because the Morgan does not have any conservation scientists, NICS typically handles its technical analysis work, as it does for other New York area museums without these resources. Simultaneously, the Yale team began gathering data about its own deck.

In mid-June 2021, the technical study expanded to include tarocchi decks in two Italian collections. NICS scientist Federica Pozzi—who had by then moved to Italy to serve as head of scientific laboratories at the Centro per la Conservazione ed il Restauro dei Beni Culturali in Turin “La Venaria Reale”—engaged those new partners. Scientists from the Art Institute of Chicago and the National Gallery of Art in Washington were also enlisted to provide additional analysis. All institutions shared their data and access to technical equipment. Team members began to meet via Zoom every month, as they have been doing ever since.

“When conservators, curators, and conservation scientists work together,” said Lemay, “we discuss what to analyze, what tools to use, and the significance of the data obtained. It is an ongoing, iterative process. Through regular conversations we are able to place our discoveries in context and dive deeply into understanding these fascinating objects.”

Technical analysis

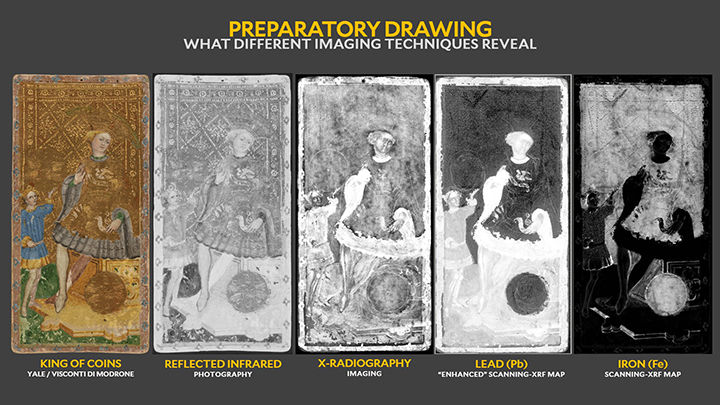

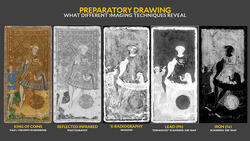

The team determined that the cards, which are approximately 7 x 3 1/2 in. (18 x 9 cm), were built on a rigid support made with several layers of paper. A series of underdrawings on the topmost layer—made with lead-containing material, iron gall ink, and simplified incised lines—provided an outline of the design for the artist to follow.

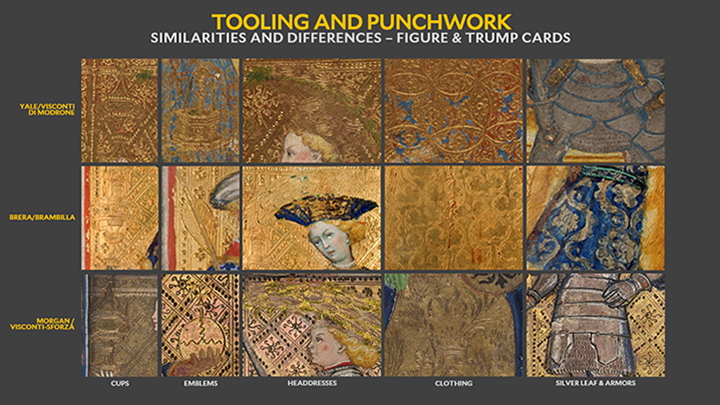

A layer of bole (red clay) was painted on the background to adhere the gold leaf and oro di metà, a gold-and-silver leaf laminate. The metal-leaf backgrounds were decorated with tooling and punchwork. Gold leaf is also found in the details of the four suits.

The colorful images were painted using the tempera technique and translucent glazes. Six faint watermarks on the backs of some Yale cards closely resemble watermarks that are documented and reproduced in two databases, supporting a recent proposal dating the cards to 1441–42.

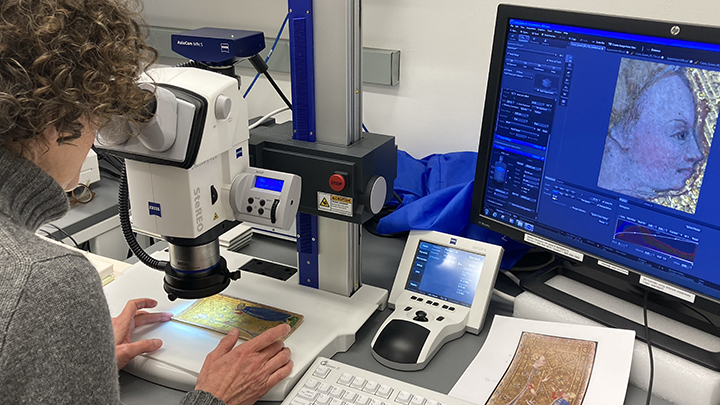

The scientific equipment and expertise at IPCH and Yale Library made the on-campus study of the Visconti di Modrone and Morgan cards possible. Raking light photography and other photographic techniques provided clues about the cards’ surfaces. Under a microscope, brush strokes, overlapping paint layers, losses that reveal underdrawing lines, and punchwork shapes and patterns are visible.

A macroscale understanding of the materials required more sophisticated technology, however.

Scanning XRF spectroscopy provides a nondestructive method for identifying a sample’s elemental composition by exciting atoms to emit X-rays. The energy and intensity of the emissions provide scientists with information about the type and relative amount of each element present. This information then allows them to infer what pigments are in an artwork and how they are distributed. XRF analysis permits researchers to see what lies in and within underlying layers.

“The scanning XRF allows us to generate maps that show the distribution of different elements on the surface of the cards,” Lemay said. “For example, we know where all the gold is, we know where the silver is. By looking at the maps and seeing where the elements overlap, we can make assumptions about pigments. Areas where the sulfur and mercury maps coincide, for example, suggest you might have vermilion there—a pigment made by combining mercury and sulfur.

“XRF does not allow you to definitively identify pigments, however,” Lemay added. “You need another method to confirm your suspicions. These maps only tell you that the elements are there but not if they are chemically combined in a compound, for example, or layered.”

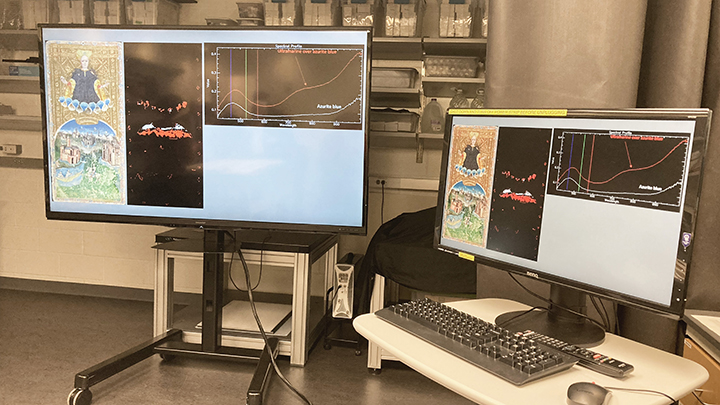

Team members also relied on several additional types of noninvasive investigation, such as Raman spectroscopy and reflectance imaging spectroscopy (RIS), to identify the pigments and colorants in the cards. The blues on the Yale cards are azurite and a mixture or layering of azurite and lapis lazuli. The yellows are lead tin yellow, and the browns are iron gall ink and a brown colorant not yet identified. The whites and blacks are lead white and a carbon-based black.

With other tests, team members focused on identifying organic colorants and types of glues and binders. Some of the testing required removal of microscopic samples and analysis with benchtop instrumentation.

To gain deeper insight, conservators on the team are planning to remake a tarocchi card, following the same techniques they have discovered through their observations and analyses.

Virtual and ongoing study

In June 2022, the Thaw Conservation Center at the Morgan Library & Museum hosted an online Tarocchi Virtual Study Day. Presenters from Yale Library, the Morgan, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Centro per la Conservazione ed il Restauro dei Beni Culturali “La Venaria Reale,” the Accademia Carrara, and Pinacoteca di Brera presented their detailed findings from studies of the tarocchi cards in their respective collections.

“These cards present wonderful opportunities for scholarship in the history of art, games, social structures, material culture, and conservation science,” Tim Young wrote in his invitation to the event. The study day received curatorial and financial support from the Beinecke Library’s Cary Playing Card Collection.

As Hark, Lemay, Pozzi, and Trujillo wrote in their paper, “Tarocchi Teamwork: An International, Multi-institutional Collaborative Research Project,” the project “benefits from institutional support, available funding, remarkably interesting subject matter, and a general bonhomie among teammates. The main recommendation for any collaborative technical study is to work with interesting people, who are respectful of each other’s strengths and foibles and are driven by a mutual enthusiasm for the study.”

The Cary Collection of Playing Cards, a collection that began with a major gift to the Beinecke Library from Mrs. Samuel H. Fisher in 1945, was later augmented when Melbert B. Cary Jr. and Mary Flagler Cary donated their collection, which included the 67 Visconti cards. Researchers and visitors at Yale regularly request these popular objects for study.

The Cary Collection contains another incomplete set of Italian tarocchi cards—16 cards from the Este deck, ca. 1450, which the Yale team hopes to study next. The team will also continue to study the cards in the Colleoni-Baglioni and Brambilla-Brera decks in the collections in Italy. Several members of the team recently presented papers on the materials and techniques of the cards at conferences in Copenhagen (April 2023) and New York City (July 2023); others are working on upcoming presentations and publications focusing on their areas of expertise. Still in the planning stages is an exhibition to be held at the Morgan Library& Museum, which will hopefully reunite portions of these three important tarocchi decks.

View all the digitized cards in the Visconti di Modrone tarocchi deck.

Watch the four-session Tarocchi Virtual Study Day.

—Deborah Cannarella

Images: Cavalier of Coins (female) and Cavalier of Coins (male), from Yale Library’s Visconti di Modrone deck; Marie-France Lemay examining the Queen of Coins card with a stereomicroscope; a comparison of Yale’s King of Coins card viewed with different imaging techniques; similarities and differences in the background decoration of cards from the three decks; a sampling of the 67 cards in the Visconti di Modrone deck; a display of data obtained from the World card in Yale’s deck, using reflectance imaging spectroscopy (RIS); Richard Hark using Raman spectroscopy to identify pigments in the tarocchi cards. All photos except for technical images and single-card images by Deborah Cannarella